About the development of Suchet's career, plays and playwrights, Poirot - and having the biggest dressing-room in West End... bricksite.com/davidsuchet

David Suchet

by Mark Shenton, Theatre.com 13.8.2007

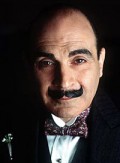

David Suchet is best known for playing Agatha Christie’s Poirot in the long-running television series, but he considers himself blessed because it hasn’t boxed him into a career corner, either in terms of typecasting or the time he has to give to it. The role has been part of his life for the last 18 years, and next year he will film yet another series. “If I do manage to do the next 12,” he says, “I will be able to leave behind me the complete works of that character, in what will have been the best part of 20 years work. That’s the first time in television history that anyone has done that. I will have done over 50 films as Poirot.” Because he has spread out his appearances in it, he has also managed to sustain a career outside of it. While much of that has been on television and film, Suchet keeps returning to his first love: the stage. But thanks to Poirot, he’s also a bankable name in the West End, where he is now back, leading the cast of The Last Confession at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket. He’s a theatre animal through and through, as Theatre.com discovered when we met the star in his dressing room at the Haymarket, which is probably the West End’s grandest.

It’s a long climb to this dressing room—and you’ve taken your time getting here.

I’ve waited 40 years to get here, but it’s been worth the wait. I mean, look at it. I’m used to even number one dressing rooms being tiny, although of course they’re usually nearer the stage. This is six flights up and is called number 10. But I’ve visited the greats here over the years, and I remember when the theatre was restored and redecorated about 10 years ago, I was shown around and they said, “One day this will be yours, Mr. Suchet.” And here I am.

Your last London stage appearance was in Once in a Lifetime at the National in 2005, in a starring role you originally played for the RSC in 1979. It was another first for you—you’d not done the National before.

Yes, it brought me to the National for the first time as a company member. I’d always wanted to go there, but it never worked out. So it was a wonderful opportunity, and I took it not necessarily just for the role. I’d played so many zonking great leads before it that when it was offered, it was an opportunity to come back to a company and not to have to take on the responsibility of the show, just for once.

The West End role you did just before it found you doing just that. Man and Boy, the Terence Rattigan play you revived, was a flop the first time it was seen, but you turned into a hit.

The West End role you did just before it found you doing just that. Man and Boy, the Terence Rattigan play you revived, was a flop the first time it was seen, but you turned into a hit.

It was wonderful. I will look back on that—if I look at the spider’s web of my career when I turn around and look at the patterns—as a big piece of the web. I did it for no other reason than the reason I became an actor in the first place—to serve writers. I became an actor partly because I failed as a doctor. My father was one, but I never really had the academic qualifications. But what made me really want to become an actor was not anything to do with acting but rather with the thought, when I was in the National Youth Theatre, about what an extraordinary position actors had in being able to interpret roles for writers who wanted to give their work away to them to interpret, rather than writing a novel. Why would someone do that? So I did Man and Boy solely for Terence Rattigan, my writer. I wanted to give his play, which he considered possibly his most important play, another chance. Having read Geoffrey Wansell’s book about his suffering over how the play was received and not cast as he wanted it, I wanted to do it. I was really ready to play this character that many have turned down… including me. I had been offered the play four times in my career and turned it down, but it was the time to do it. You played that role with a total lack of sentimentality.

Rattigan said that he created the devil incarnate in that character, and I decided to make him completely irredeemable. I didn’t want him to be liked at all.

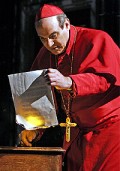

But now you’re in a play, based on real-life facts, playing a Catholic Cardinal involved in the papal succession in Rome in 1978, who is seeking a kind of redemption of his own.

But now you’re in a play, based on real-life facts, playing a Catholic Cardinal involved in the papal succession in Rome in 1978, who is seeking a kind of redemption of his own.

In a sense he is. The play works on two levels, I think. On the one hand, it’s a whodunit based on a conspiracy theory about the short reign of the liberal Pope John Paul I, who died just 33 days into his reign, that the writer Roger Crane gathered together and was fascinated by, being also a lawyer. But the other part of the play is the journey of doubt that this cardinal, Giovanni Benelli, goes on. The world has heard nothing of him, but he actually got within five votes of becoming the pope himself. Yet who was he? The conservatives at the Vatican walled him out, and then we had Pope John Paul II. But he would have been very radical. His journey of doubting—rather than finding—was very appealing to me as an actor, because I always like to work on multi-layers. I don’t just want to play good or bad, or faith or doubt, but I want to find the person within. The intention is always to seek out the person within that then becomes on the outside something that is maybe very different; I like to play inside the outside. I’m not so much playing a cardinal as a man who is chosen to be one and believes he is called to be one, but what I try to do is play the man.

Were you involved at an early stage in the play’s development?

Were you involved at an early stage in the play’s development?

Yes, it first came to me five years ago, but it certainly wasn’t ready then. It was brought to me with another director attached, and I said no to it. But then the playwright wrote a film version, in which the dialogue was chopped and chopped and chopped. And a friend he showed it to said to him, “You know who should play this? David Suchet.” But he said I had already seen the play and had turned it down. His friend asked if I’d seen this latest version, so it was sent to me again. I thought it still needed work, so I went to New York and spent a couple of weeks there on two different occasions working with him, and I started to believe in the piece and therefore the writer. I realised I could do something with the character, and offered to help the playwright get it on. That’s what I do. I love writers.

It’s rare for actors to be involved at that level.

It’s very rare, but I really loved it. I think I’ve got to a stage in my life, looking back over the last five years, where I really like to be involved in everything now, rather than just coming in and being an actor for hire. I am now associate producer with Poirot, so I am very much involved in the scripts and what we call the tone meetings, and I work with the director and producers on a day-to-day basis. I think I have found something that really expands me and I think I can offer something to and properly serve the writers.

How did The Last Confession finally get produced?

I took it to Duncan Weldon, who was originally going to be involved in the first version. And it just so happens that the director David Jones rang Duncan, and said he hadn’t done a play in England for a long time and asked him if there was anything around. I’d worked with David with the RSC at the Aldwych in 1975, and immediately said, “This is our man.” He’s the man to do the big-cast play—there are not many left who are able to do this sort of play. But to do it commercially is crazy. Nobody in their right mind would put on a religious sort of play by a first-time writer with 25 actors in the West End. But it’s great that we are doing it. That’s what I’m about.

It’s quite a risk.

Yes, but why not? If we don’t take risks in this business, we’ll never get anything on. If we totally rely on the subsidised theatre, we’re not going to hit what I call the G.P.—the general public. I could go to the RSC or National for the rest of my life, and I may do so again later, but while I have a profile from TV, movies and even the radio, then I can reach the ordinary public, who wouldn’t see it at the RSC because they wouldn’t go there.

The success of Poirot certainly gives you box office clout.

The success of Poirot certainly gives you box office clout.

It has done that for me, and I’m forever grateful. Never bite the hand that feeds you.

But it has also given you artistic freedom.

What it does, in acting terms—and basic speak—is it also gives you fuck-you money. It means you can say no. That’s what it buys you. It gave me the profile and I just go on my knees with gratitude for it. Because Poirot is a character and not me, it allows me to move throughout the medium as different people and not get stuck.

Despite the success you’ve had elsewhere, you’ve kept faith with the theatre.

That’s very deliberate. I’ve had many, many chances to cross the Atlantic, and I have done the odd Hollywood film and loved it, but I want to come back all the time because I believe I am British, I was born here and theatre is in my blood. If I was go to there permanently I don’t believe I would be fulfilled, and I don’t believe it would be right. There are many actors out there who are wonderful stage actors and won’t come back, and I think it’s a great shame. It was a deliberate choice of mine not to get seduced by that—though I was. I was very seduced by the thought of it.

Tell me about the tour you did with this piece before you came to London.

It was such a treat, and it’s very important that leading actors should go on tour. There’s a hungry theatre audience out there who can’t necessarily come to London. So we should never get above ourselves and say we won’t tour—we have to go out there. We’re travelers and we’re servants of the playwright and always dependent on our audiences. We should never forget that, ever. If we do, we might as well play in front of a mirror and stay at home. I will never stop doing theatre, as long as I’m healthy enough.

2007 © All rights reserved